The Mob’s Reel: ‘Blade Runner 2049’ Is a Challenging, Riveting Film

The Mob’s Reel is a film column that features reviews and essays covering everything from the latest blockbusters to standout indies.

REVIEW

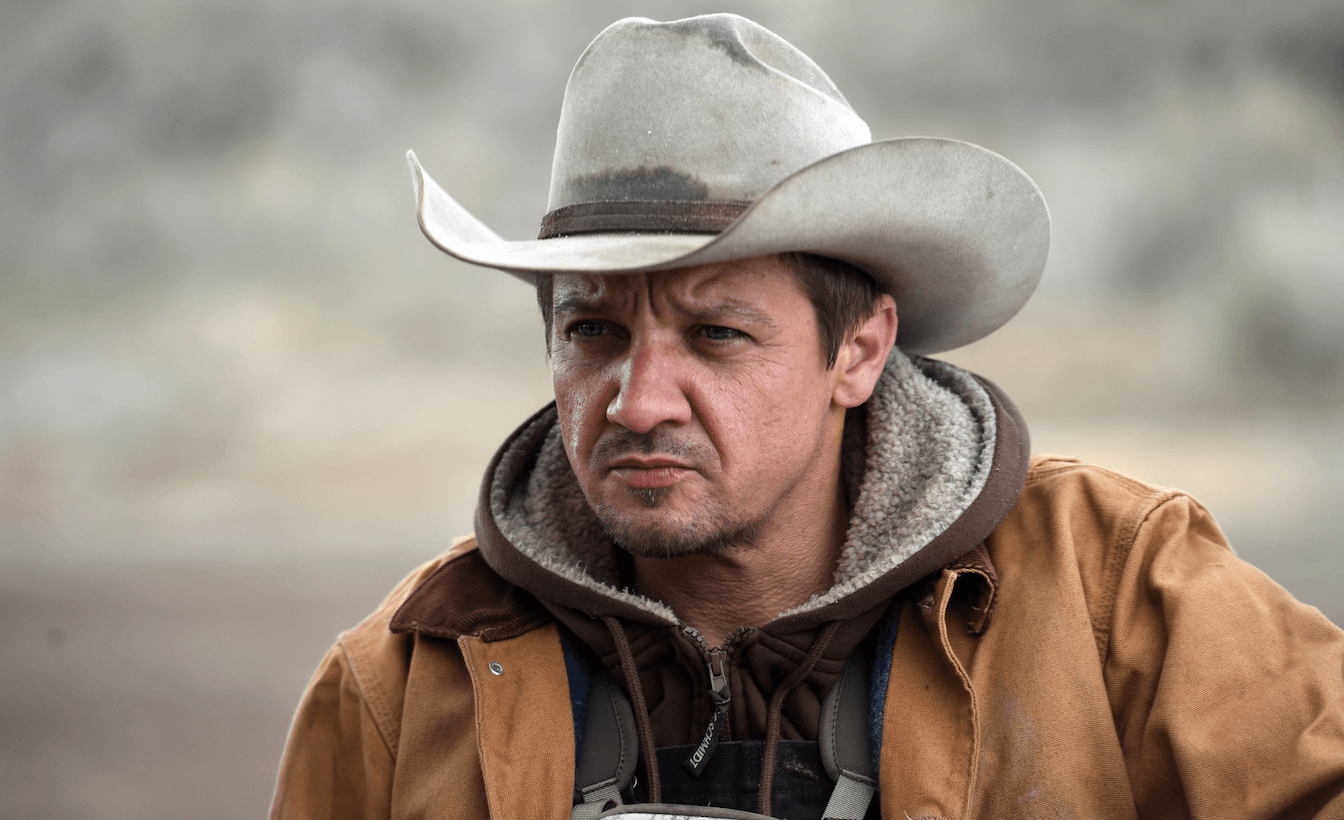

Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 is a thoughtful, meditative sequel that furthers the first film’s exploration of humanity, artificial life, and free will. Ridley Scott’s original Blade Runner made little impact during its 1982 theatrical run, but it has since been reassessed as a science fiction classic, especially after the release of Scott’s definitive version of the film, the 2007 “Final Cut.” Early box office reports reveal weak numbers for Blade Runner 2049, which shouldn’t come as a shock considering it’s a long and difficult film that isn’t focused on easily-digestible spectacle. I do hope positive word of mouth brightens the film’s box office prospects, because it’s a complex and gripping cinematic experience that deserves to be seen on the big screen.

In 2049 California, Officer K (Ryan Gosling) is tasked with hunting and killing rogue bioengineered humans called replicants. During a seemingly routine case, the discovery of a startling secret leads him on a mission to find Rick Decker, a former cop who has been missing for thirty years.

Playing an obedient, newer model replicant, Gosling is reserved and steely, but there are heartbreaking glimpses of a humanity he’s not quite sure he even has. There are a longing and loneliness that subtly bubble to the surface, particularly during his interactions with Joi (a terrific Ana de Armas), his holographic AI girlfriend. In many ways, it’s an approximation of a relationship; neither character is a human being in the traditional sense — even less so with Joi, who has no tangible body — but there’s something sincere between them, despite Joi essentially being a commercial product purchased to inject some life into K’s lonely existence. When her holographic self occasionally flickers and falters, we’re left to wonder whether she is truly sentient or just an exceptionally lifelike product. Regardless, it reveals something deeper within K than his designed purpose might suggest, and Gosling gives an understatedly powerful performance as a replicant questioning all he knows.

Harrison Ford’s Rick Decker, the protagonist of the 1982 original, doesn’t appear until late in the film, but he plays an instrumental role before he even shows up on screen. When K and Decker finally meet, Ford seamlessly slips back into the role he played 35 years ago, doing solid work as a grizzled, hermetic version of the character. The performances are strong across the board, with small but memorable roles by Dave Bautista, Mackenzie Davis, and Jared Leto.

Villeneuve is one of the finest directors working today; his films are methodical and finely tuned, always featuring a strong emotional throughline. He accomplished plenty with last year’s heady sci fi film Arrival, and his work here is even more remarkable. The world of Blade Runner is broken and crowded. It’s steel and concrete and neon. It could have easily been too cold in the wrong hands, but Villeneuve’s questions and concerns about the human experience are intimately felt. It’s not just a film about ideas; it’s about people, whether born or manufactured.

The production design is rich and endlessly imaginative, vividly rendering the cyberpunk claustrophobia of a retro-futuristic Los Angeles. Cinematographer Roger Deakins has been doing excellent work for decades, and his previous collaboration with Villeneuve, 2015’s Sicario, was terrific. Here we see Deakins at the height of his abilities, his neon-drenched noir visuals making for what is arguably the year’s best-looking film.

Roy Batty’s “tears in rain” monologue from the 1982 original is a poignant, moving piece of cinema that has helped cement the film as an enduring classic. 2049 seems to use the emotional core of that scene as its guiding star, finding wrenching ways to examine the push-and-pull between technology and humanity. Scott laid the foundation, but Villeneuve isn’t merely playing in someone else’s sandbox. Along with screenwriters Michael Green and Hampton Fancher, he holds true to the spirit of the first film while finding new avenues to explore and questions to ask, revealing both shattering bleakness and glimmers of hope.